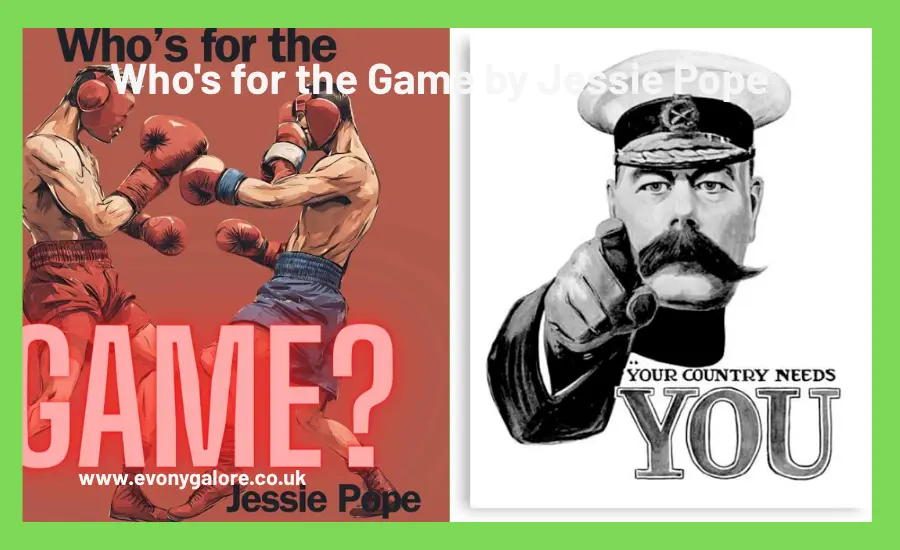

Who’s for the Game by Jessie Pope: A Comprehensive Analysis of War Propaganda Poetry

The landscape of World War I literature encompasses a diverse spectrum of voices, from the haunting battlefield verses of Wilfred Owen to the patriotic recruitment poetry of Jessie Pope. Among Pope’s most controversial and historically significant works stands “Who’s for the Game,” a poem that crystallized the early wartime enthusiasm of 1915 Britain while simultaneously becoming a lightning rod for criticism about the romanticization of warfare. This piece of propaganda poetry, published during a critical period when Britain desperately needed volunteers for its expanding military forces, represents a fascinating intersection of literature, politics, and social manipulation that continues to generate scholarly debate more than a century after its composition.

Understanding the context and impact of “Who’s for the Game” requires examining not only the poem’s literary techniques and rhetorical strategies but also the broader cultural moment that produced it, the biographical background of its author, and the fierce opposition it later provoked from soldier-poets who experienced the genuine horrors of trench warfare. This analysis explores how Pope’s seemingly innocent sporting metaphors masked the brutal reality of modern industrialized warfare, how her work functioned within the British government’s recruitment machinery, and why this particular poem has endured as perhaps the most infamous example of jingoistic war poetry in the English language.

The Historical Context of Jessie Pope’s War Poetry

Jessie Pope emerged as one of Britain’s most prolific patriotic poets during the First World War, contributing regularly to newspapers and magazines that served as vital conduits for government propaganda. Born in Leicester in 1868, Pope had established herself as a successful journalist and writer of light verse before the war transformed her into a controversial figure. When Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914, the nation faced an unprecedented challenge: raising a massive volunteer army without the benefit of conscription, which would not be introduced until 1916. The government’s solution involved a sophisticated propaganda campaign that enlisted writers, artists, and public figures to encourage enlistment through appeals to patriotism, masculinity, and adventure.

“Who’s for the Game” appeared in 1915, during what historians recognize as a crucial transitional period in British war enthusiasm. The initial wave of volunteers who had rushed to recruiting stations in the war’s opening months had already suffered devastating casualties at battles like Mons, the Marne, and First Ypres. The Western Front had calcified into the infamous trench system that would characterize the war, yet the full scale of industrial warfare’s horror had not yet penetrated the British public consciousness. Newspapers remained subject to strict censorship, and the government actively suppressed information about casualty rates and battlefield conditions. Into this information vacuum stepped poets like Pope, whose verses painted warfare as a glorious sporting contest rather than mechanized slaughter.

The poem’s publication coincided with the Second Battle of Ypres, where German forces first deployed chlorine gas on a large scale, and with growing concern among military planners about maintaining recruitment levels. Pope’s work appeared in newspapers with mass circulation, particularly the Daily Mail, ensuring that her message reached millions of potential recruits. The British government’s Parliamentary Recruiting Committee actively encouraged such literary contributions, recognizing that emotional and cultural appeals often proved more effective than straightforward factual arguments. Pope became, whether consciously or not, an instrument of state policy, using her considerable literary skill to manufacture consent for a war that would ultimately claim nearly a million British lives.

Literary Analysis and Poetic Techniques in “Who’s for the Game”

The poem’s opening question, “Who’s for the game, the biggest that’s played?” immediately establishes Pope’s central metaphor, framing World War I as a sporting competition rather than mortal combat. This rhetorical choice reflects deeply embedded cultural assumptions in Edwardian Britain, where public school education emphasized character development through team sports, and military service was often portrayed through the lens of athletic competition. The metaphor extended beyond mere linguistic convenience; it tapped into powerful social codes about masculinity, fair play, and the “playing fields of Eton” mythology that supposedly won Britain’s wars.

Pope employs a simple ABAB rhyme scheme throughout the poem, creating a sing-song quality that makes the verses memorable and easily reproducible. This technical choice served propaganda purposes perfectly, as the poem could be quickly memorized, recited, and disseminated through oral tradition alongside its printed distribution. The regular meter and predictable rhymes create a sense of confidence and certainty, never allowing space for doubt or questioning. Each stanza builds toward a rhetorical question designed to challenge the reader’s courage and manhood, employing peer pressure and shame as motivational tools.

Key Literary Devices and Their Propaganda Function:

- Sporting Metaphors: Pope consistently describes warfare using language borrowed from cricket, rugby, and other British sports. Phrases like “the biggest that’s played” and references to the “red crashing game” transform battlefield carnage into athletic excitement, deliberately obscuring the reality of machine guns, artillery barrages, and poison gas that characterized actual combat conditions.

- Direct Address and Rhetorical Questions: The poem repeatedly uses “Who’s for…” constructions that directly challenge readers, creating a sense of personal confrontation. This technique places readers in an uncomfortable position where failing to volunteer becomes equivalent to failing a public test of courage and character.

- Binary Oppositions: Pope structures the poem around stark contrasts between courage and cowardice, action and passivity, men and boys. These simplistic divisions eliminate nuance and present readers with a false choice designed to channel them toward enlistment rather than critical thinking about the war’s causes or conduct.

- Appeals to Youth and Vigor: The poem specifically targets young men by emphasizing physical strength, adventure, and the shame of remaining behind while others fight. Pope asks, “Who’ll grip and tackle the job unafraid?” and contrasts those who will join up with those content to remain in safety, creating powerful social pressure particularly effective in tight-knit communities where public honor mattered intensely.

The poem’s tone remains relentlessly upbeat and confident, never acknowledging doubt, suffering, or death except in the most euphemistic terms. This tonal consistency reinforces the propaganda message by presenting military service as unambiguously positive and heroic. Pope’s choice to exclude any reference to the actual experiences of soldiers, the mud, terror, mutilation, and psychological trauma, represents a deliberate editorial decision that served recruitment needs but bore no relationship to battlefield reality.

The Controversy and Critical Reception

The most famous critique of Jessie Pope’s war poetry came from Wilfred Owen, one of the war’s greatest poets, who originally intended to dedicate his masterpiece “Dulce et Decorum Est” to her. Owen’s poem, which graphically depicts a soldier dying from a gas attack, directly refutes the “old Lie” that dying for one’s country is sweet and fitting, a lie that poems like “Who’s for the Game” propagated. Although Owen ultimately changed the dedication to “a certain Poetess” rather than naming Pope explicitly, literary historians have long understood her as the target of his anger. Owen’s response crystallized the bitter resentment soldier-poets felt toward civilian writers who encouraged enlistment while remaining safely removed from the war’s actualities.

The divide between Pope’s cheerful propaganda and soldier-poets’ testimonies from the trenches reveals a fundamental disconnect in British wartime culture. While Pope wrote of games and glory, Siegfried Sassoon composed bitter satires attacking the home front’s ignorance, and Isaac Rosenberg documented the dehumanizing horror of industrial warfare. This literary split mirrored a broader social division between those who experienced combat and those who consumed romanticized versions of it in newspapers and poetry. The controversy surrounding Pope’s work intensified after the war as the full scale of casualties became known and public opinion shifted toward viewing the conflict as a tragic waste rather than a glorious adventure.

Modern critics have debated whether Pope deserves harsh condemnation or whether she simply reflected the limited information and sincere patriotic beliefs prevalent in her time. Some scholars argue that Pope genuinely believed she was serving her country and could not have anticipated how misleading her portrayals would prove. Others contend that even by 1915 standards, the gap between her sporting metaphors and reports filtering back from the front represented a willful distortion that prioritized propaganda effectiveness over truthfulness. The debate continues to engage students and scholars examining the ethics of war literature and the responsibilities of writers during national crises.

Comparative Analysis: Pope Versus the War Poets

| Aspect | Jessie Pope | Wilfred Owen | Siegfried Sassoon |

| Perspective | Civilian/Home Front | Soldier/Front Line | Officer/Combat Veteran |

| Tone | Enthusiastic, encouraging | Bitter, compassionate | Satirical, angry |

| Purpose | Recruitment propaganda | Truth-telling, memorial | Anti-war protest |

| Imagery | Sporting metaphors, adventure | Graphic physical suffering | Institutional critique |

| Audience | Potential recruits | General public, posterity | Home front civilians |

| Legacy | Controversial, criticized | Canonical, respected | Admired, influential |

This comparative framework illustrates how radically different poetic responses to World War I could be, depending on the author’s relationship to combat. Pope’s work represents what scholar Paul Fussell termed the “theater of war” tradition, which presented conflict as a dramatic spectacle. In contrast, Owen and Sassoon pioneered what might be called testimonial or witness poetry, which prioritized experiential authenticity over propaganda utility. The tension between these approaches has shaped war literature ever since, with contemporary readers generally favoring the unflinching realism of combat veterans over the patriotic fervor of civilian propagandists.

The Role of Gender in Reception and Criticism

Jessie Pope’s gender has complicated critical assessment of her work, with some scholars arguing that misogyny has intensified the harsh judgments directed at her poetry. Male propagandists produced equally misleading and jingoistic material during World War I, yet few have been subjected to the same sustained criticism that Pope endures. The figure of the woman who encourages men to fight while remaining safely at home carries particular cultural resonance, tapping into anxieties about female power, sexual dynamics, and the gender hierarchies that warfare disrupts and reinforces simultaneously.

The image of women distributing white feathers to young men not in uniform, a practice that shamed supposed cowards into enlisting, became infamous during World War I and has been retrospectively associated with Pope’s poetry, even though no evidence suggests she personally participated in such activities. This conflation reveals how individual women’s voices became symbolic of broader social pressures that drove recruitment. Pope’s poetry gave literary expression to a culture of shame and honor that operated through multiple mechanisms, from recruitment posters to peer pressure to family expectations. Understanding her work solely as individual expression misses how it functioned within larger systems of propaganda and social control.

Contemporary feminist scholars have begun to reassess Pope’s position, noting that she operated within constrained professional circumstances where patriotic writing offered one of the few ways for women to gain public voice and income during wartime. While this contextualization does not excuse the misleading nature of her propaganda, it complicates simplistic narratives that present her as uniquely villainous. The debate over Pope’s legacy thus extends beyond literary criticism to encompass larger questions about women’s agency, professional survival, and moral responsibility during wartime.

Educational and Cultural Legacy

“Who’s for the Game” has become a standard text in British secondary education, typically taught alongside Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” to illustrate contrasting perspectives on World War I. This pedagogical pairing serves multiple functions: it demonstrates how literature can serve political purposes, illustrates the importance of authorial perspective, and encourages critical thinking about propaganda’s techniques and effects. Students analyzing Pope’s poem learn to identify rhetorical strategies, question emotional manipulation, and consider the ethics of persuasive writing during national crises.

The poem’s continued presence in curricula ensures that each new generation encounters these questions about literature’s relationship to truth, the responsibilities of writers during wartime, and the ways that language can obscure or reveal reality. Teachers use Pope’s work to initiate discussions about media literacy, critical thinking, and the importance of seeking multiple perspectives on historical events. In this sense, despite or perhaps because of its controversial nature, “Who’s for the Game” continues to perform valuable educational work by serving as a cautionary example of how skillful writing can be deployed to misleading ends.

Conclusion:

More than a century after its publication, “Who’s for the Game” remains relevant not as a successful work of art but as a historical document that illuminates propaganda’s mechanisms and the dangerous gap between wartime rhetoric and battlefield reality. Jessie Pope’s poem succeeded brilliantly at its intended purpose, encouraging enlistment through emotional manipulation and sporting metaphors while failing catastrophically at representing warfare’s actual nature. This dual legacy makes the work invaluable for understanding how societies mobilize for war and how literature can serve both truthful and deceptive purposes.

The controversy surrounding Pope’s poetry ultimately raises questions that extend far beyond one woman’s verses to encompass fundamental issues about art, politics, and moral responsibility. Contemporary readers confronting “Who’s for the Game” must grapple with uncomfortable truths about how easily populations can be manipulated through appeals to courage, honor, and masculine pride. They must also consider whether different standards should apply to wartime writing versus peacetime literature, and whether sincere patriotic belief excuses the propagation of dangerous falsehoods.

As we continue to face armed conflicts and propaganda campaigns in the twenty-first century, Jessie Pope’s World War I recruitment poetry offers crucial lessons about skepticism, critical reading, and the importance of seeking voices from multiple perspectives, particularly those with direct experience of the realities that distant observers romanticize. The poem endures not because it represents great literature, but because it exemplifies the consequences when skilled writers place their talents in the service of persuasion, divorced from trut,h a warning that remains eternally relevant regardless of the era or conflict in question.